Ávarp við opnun Tengslanets-ráðstefnu II – Völd til kvenna

Ávarp Dr. Herdísar Þorgeirsdóttur prófessors við setningu ráðstefnunnar Tengslanet – II: Völd til kvenna: Fjármál, frami, fjölskyldur – 27. maí, 2005. © “Mein Herz brennt” Velkomnar á aðra tengslanets-ráðstefnu sem haldin er á Íslandi á 21. öldinni– frábært að hitta ykkur aftur og sumar í fyrsta sinn en vonandi ekki það síðasta. Tengslanetið er í raun og veru staðfesting á því að konur eru að gera sér betur og betur grein fyrir því að það færir okkur enginn völdin – VIÐ VERÐUM AÐ TAKA VÖLDIN SJÁLFAR. Maureen Reagan (dóttir Ronalds Reagan forseta Bandaríkjanna) sem kom til Íslands fyrir mörgum árum og sat fund með íslenskum konum um jafnréttismál sagði: “Mér finnst jafnrétti vera náð þegar konur eru komnar til valda sem eru eins vonlausar og margir karlar sem eru þar fyrir!” Fyrsta tengslanets-ráðstefnan sendi frá sér ályktun þar sem skorað var á stjórnendur íslenskra fyrirtækja að taka þegar til við að leiðrétta rýran hlut kvenna í stjórnum og æðstu stjórnunarstöðum innan fyrirtækjanna enda hafi konur aflað sér menntunar og reynslu sem atvinnulífið hefur ekki efni á að vannýta með þeim hætti sem nú er gert. Þó að við höfum ekki beitt okkur fyrir því að upplýsingar um árangur einstakra fyrirtækja yrði birtur opinberlega, eins og til stóð, er ljóst að ýmislegt hefur gerst á síðasta ári sem er vísbending um breytingar. Kraftmikil femínísk umræðu í þjóðfélaginu – í háskólum – félagasamtökum og meðal kvenna í öllum aldurshópum og á hinum fjölbreyttustu sviðum samfélagsins – hefur örugglega átt þátt í því að í fyrsta sinn er kona rektor Háskóla Íslands; kona sem er fyrirlesari hér í dag er Þjóðleikhússtjóri; konur hafa nýlega verið ráðnar forstjórar stórfyrirtækja og hér er kona sem situr í stjórn nokkurra stórfyrirtækja –– hér er líka kona sem vann mál fyrir hæstarétti sem markar tímamót í baráttu gegn launamuni – og hér eru margar fleiri sem hafa vakið verðskuldaða athygli fyrir störf sín en eðli máls samkvæmt eru hér einnig hugsanlega of margar konur, sem hafa ekki fengið þá umbun og virðingu sem þær eiga skilda. Loks má ekki gleyma því að einn fyrirlesari frá því á fyrsta tengslanetinu er nýkjörin formaður annars stærsta stjórnmálaafls landsins – þungavigt í heimi karlanna eins og þeir segja með lotningu sjálfir. Harvardprófessorinn og ofurhippinn Timothy Leary sagði: “Konur sem sækjast eftir jafnrétti við karlmenn skortir metnað!” Ég veit ekki hvort hann hefur öðlast þess sýn 2 á sýru-trippi en hann var eins og kunnugt er ötull talsmaður LSD – eða hvort hann hefur bara verið gæddur miklu innsæi. En það sem mest er um vert – við erum komnar hingað saman – til að halda áfram baráttunni því hana heyr enginn annar fyrir okkur! Svona ráðstefna er stökk í baráttunni sem öðru jöfnu er skref fyrir skref barátta: tvö áfram og eitt aftur á bak. Það er samt breyttur tónn í þjóðfélaginu. Jafnréttismál eru í tísku, þau eru ekki afgreidd sem eitthvert “kerlingavæl” en félagsmálaráðherra sagði mér að hann hefði verið kallaður “kellingakjaftur” upp á færeysku þegar hann var í Færeyjum að ræða íslensku fæðingarorlofs-lögin í vetur. Jafnréttismál eru ekki mjúk mál heldur dauðans alvara sem varða alla – frelsi konu er frelsi manns og það hvernig konum reiðir af hefur úrslitaáhrif á hvernig börnum reiðir af og því hvernig þjóðfélaginu reiðir af sem og heiminum öllum. En fordómarnir eru víða. Skáldkonan Margaret Atwood setti fram þessa spurningu: “Er femínisti brussuleg, óaðlaðandi og hávær kona eða sú/sá sem trúir því að konur séu líka manneskjur? Ég fylki mér í flokk þeirra sem taka undir síðari kostinn,” sagði hún og ég tek undir með henni. Baráttan um völd til kvenna er mannréttindabarátta sem skilar sér ef árangur næst til barna og allra annarra í samfélaginu. Og hver eru verkefnin sem bíða okkar núna út næstu öld? Þau eru að halda áfram baráttunni á grundvelli hins lagalega ramma, jafnréttislaga, evrópskra tilskipana, stjórnarskrár og almennra mannréttinda – og skapa konum enn betri vígstöðu til að ná rétti sínum. Mörg af þeim málum sem eru mikilvæg verða rædd hér í dag svo sem launajafnrétti og samræming fjölskyldulífs og hinnar hörðu samkeppni á vinnumarkaði. Þessi mál brenna á konum en maður heyrir aldrei karlmenn örvænta yfir því hvernig þeir eigi að samræma vinnuna og fjölskyldulífið. Við skulum ekki láta málamyndajafnræði villa okkur sýn eins og útlenda blaðamanninum, sem kom til Burma og tók eftir því konurnar gengu allar á undan körlunum – eftir aldalanga undirokun. Hann spurðist náttúrulega fyrir um þetta og fékk svarið: “Þetta er jarðsprengjusvæði frá því í stríðinu!” Það er ekkert fengið með lögum sem stuðla að jafnrétti á vinnumarkaði þegar konur axla enn þá hitann og þungan af barnauppeldi og heimili. Það eru önnur mál og ekki síður brýn! Eitt er að berjast gegn klámvæðingu, sem tröllríður vestrænum samfélögum. Hvorki klám, hatursfull orðræða né misbeiting fjár til 3 að kæfa raddir annarra voru þau markmið sem tjáningarfrelsinu var ætlað að tryggja. Gloria Steinem sagði að klám fyrir konur væri eins og áróður nasista fyrir Gyðinga. Konum – og börnum líka – stafar jafn mikil ógn af því að klámvæðing sé álitin eðlilegur þáttur í samfélaginu á sama hátt og konum í ríkjum íslam af bókstafshyggju þeirrar trúar. Baráttan gegn mansali er eitt stærsta mannréttindamál samtímans – tugir þúsundir kvenna og barna eru fórnarlömb þessa nútíma þrælahalds. Jafnréttismál eru mannréttindi en mannréttindi eru ekki einhver útkjálki á einhverri hugmyndafræði heldur grundvöllur þess að hægt sé að stuðla að betra og réttlátara samfélagi og því eitthvað sem allir geta sameinast um – eða ættu að geta sameinast um. Þessi ógnvekjandi vandamál sem hér hafa verið nefnd koma okkur öllum við – samþætting jafnréttissjónarmiða, baráttan fyrir launajafnrétti og jafnri stöðu almennt hangir saman við alla baráttu á sviði mannréttinda þar sem jafnrétti er grundvallaratriði. Þeir sem berjast fyrir jafnrétti snúa aldrei baki við lýðræðislegri baráttu gegn hvers kyns harðstjórn og valdníðslu hvar sem hún er og hvernig sem hún birtist – hvort sem það er kynbundið ofbeldi, umskurður stúlkubarna, barnaklám, heimilisofbeldi – eða ofbeldi yfir höfuð. Sagan sýnir okkur að í raunverulegri mannréttindabarráttu er meira um fórnir en um sigra. Og þótt við gleðjumst yfir velgengni þeirra sem ná frama er ástandið í jafnréttismálum mælt út frá stöðu þess stóra hóps sem enn líður og enn bíður – þreyir þorrann án umbunar – jafnvel í vonleysi. Þegar sá hópur minnkar þá er hægt að tala um raunverulegan árangur. Þegar örlög stúlkna eins og Lilju heyra sögunni til en hún var fátæk stúlka úr uppflosnuðu sovésku samfélagi, sem stökk af brúnni yfir hraðbrautinni í Malmö eftir að hafa verið hneppt í kynlífsánauð. Það var karlmaður sem gerði um hana ógleymanlega kvikmynd um sem bar nafnið Lilja Forever. Ég var aðeins í hálftíma fjarlægð frá þessari brú þar sem hún skildi eftir litla máða passamynd af brúarhandriðinu sem hún stökk af. Sænski leiksstjórinn Lukas Moodysson lýsti ömurlegum veruleika kynlífsánauðarinnar með því að beina linsunni stöðugt að andliti þeirra sem voru að níðast á henni og í bland við tryllta tónlist þýsku hljómsveitarinnar Rammstein með laginu “hjarta mitt brennur” – er kynt undir allt litróf tilfinningaskalans. Karlkyns kollegar gefa gjarnan það ráð að maður eigi aldrei að biðjast afsökunar. Ég er ekki alveg sammála því en samt ætla ég ekki nú að biðja ykkur afsökunar á því að minnast á Lilju forever – sem er nokkurs konar nútíma útgáfa af litlu stúlkunni með 4 eldspýturnar – og verri útgáfa – hjarta mitt brennur þegar ég hugsa um myndina á baksíðu Sydsvenskunnar kaldan vetrardag – ljósmynd af fótsporum Lilju í moldinni í keri á himinhárri brúnni þaðan sem hún stökk. Hún skildi eftir litla mynd til þess að við myndum ekki gleyma – saga hennar er ekki afmörkuð í tíma eða rúmi – fremur en ranglætið sjálft. Og ranglætið er ekki einn afkimi í einhverjum sálarkytrum út í heimi – heldur hluti af tilverunni sem þrífst við kringumstæður sem við getum bæði mótað og breytt – og aðstæður sem eru oft nær okkur en mætti ætla – og láta ekki meira yfir sér en lítil, máð passamynd – sem aldrei nær á breiðtjaldið. Það er okkar að varpa ljósi á þennan veruleika. Styrkur okkar í jafnréttisbaráttunni – felst ekki í því hvað við gerum heldur hvað við ákveðum að gera. Ég set hér með ráðstefnuna Tengslanet –II völd til kvenna – megi hún verða næsta skref okkar í göngu til réttlátara samfélags.

Bókin Journalism Worthy of the Name komin út

Bók Herdísar Þorgeirsdóttur, Journalism Worthy of the Name: Freedom within the Press and the Affirmative Side of Article 10 kom út hjá Brill. Áður hafði doktorsritgerð Herdísar verið gefin út af lagadeild Lundarháskóla en nýja bókin (600 bls.) byggir að miklu leyti á fyrra verki.

Bók Herdísar Þorgeirsdóttur, Journalism Worthy of the Name: Freedom within the Press and the Affirmative Side of Article 10 kom út hjá Brill. Áður hafði doktorsritgerð Herdísar verið gefin út af lagadeild Lundarháskóla en nýja bókin (600 bls.) byggir að miklu leyti á fyrra verki.

Umsögn prófessors Kevin Boyle um bókina: “..an innovative and impassioned treatment of a central problem of our time.”

A speech for Vigdís Finnbogadóttir / Dialogue of Cultures

Flutti fyrirlestur til heiðurs Vigdísi Finnbogadóttur í Háskóla Íslands á ráðstefnunni “Dialogue of Cultures, hinn 14. apríl 2005. Magnús Magnússon sjónvarpsmaður stýrði fundinum.

Fyrirlestur til heiðurs Vigdísi Finnbogadóttur

Professor Dr. Jur. Herdís Thorgeirsdóttir – Lecture for Vigdís Finnbogadóttir – Dialogue of Cultures – University of Iceland – 14 April 2005

Tolerance, Pluralism and Broadmindedness An unattainable goal?

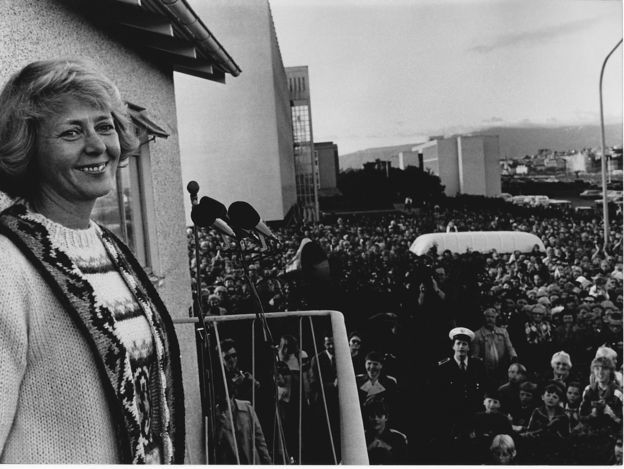

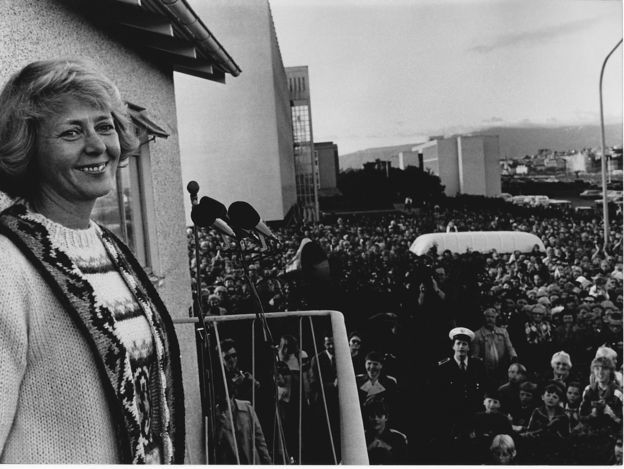

Just two weeks ago a group of women lawyers got lost in the main building of the Council of Europe – in the endless corridors of the 64 000 square meters curved building, the so-called Palais de L’Europe – while looking for a coffee shop – – and symbolically when we managed to find the right track – a captivating blonde woman smiled from a framed photograph on the wall – placed above a Xerox machine – signifying energy and optimism. This was Vigdís Finnbogadóttir around the time she was elected president in the year of 1980 – a day which many never forget – and I felt as proud when I pointed out her photo as I did when I passed by her house with my younger sister the day after she was elected and she was taking out the garbage wearing her famous woolen suit. We greeted her – by waiving and saying congratulations. She smiled at us and said: congratulations to you too! She won the elections and it was a victory for women in Iceland and women around the world.

The election of this woman, the first woman to be elected head of state in democratic elections in the world was not the result of a tremendously positive and women-friendly media at the time – it is more likely that she rode on the wave of feminism, a call for equality, which reached its peak two years later with the Women’s list for parliamentary elections.

These events in the early nineties put Iceland on the map. Vigdis became a symbol of optimism for millions of women – to the outside world her election must have seemed to be the outgrowth of an extremely enlightened electorate – tolerant of new waves and broadminded enough to accept them.

As a matter of fact the time around the 1980s was also a period in Strasbourg where the European Court of Human Rights was handing down one of its most remarkable decisions with regard to the role of the media in a democratic society. This was a process of transformation from a formal, positivistic vision of the law to a substantive, natural vision of law. The Court was looking at the problem connoting a kind of morality in the concept of freedom of the press – envisioning the concept of press freedom in light of the right of the public in democratic society to a responsible media – this marked a departure from looking at the law as devoid of any connection to morality or abstract concepts like democracy. The rhetoric of press freedom became to mean more than simply the duty of the state not to interfere with journalism unless it crossed the boundaries of defamation – the Court had embarked the jurisprudence on a long journey to an uncertain destination – perhaps not even realizing the impact that its decision might and would have – the Court at this time gave hope to the role of journalism and the media in democracy like the election of Vigdis Finnbogadottir had given hope to women in many countries – that they too might succeed in politics in a male dominated world.

In the famous court case concerning press freedom that I am referring to here the European Court of Human Rights spelled out what journalism really meant, why freedom of expression is so important for the press and its journalists – and that the press, independent of whether printed press like newspapers or broadcasting, had duties to the community – and if the press would not fulfill that duty than demcratic society would not survive, let alone prosper and each individual as a significant, constitutent member of that society not only deserved respect from the press independent of ethnic origin, sex or social status but also had a right to be informed by the press – not only to be able to participate in elections and make informed decisions but also because the media moulds individuals perhaps more than any other institution in society.

Depending on the cases that came before it the Court in Strasbourg gradually elaborated on the concepts of tolerance, pluralism and broadmindedness in relation to the two variables surrounding press freedom: democratic society and individual dignity. So the Court in Strasbourg just like President Vigdis became a role model and a trend setter – often surpassing any of the domestic courts of the member states of the Council of Europe in its elaborate understanding of the role of the press – and its jurisprudence – its moral reading of the law of the human rights Convention forced the market oriented European Union to adopt its own human right agenda. Just like the European Convention was inspired by the Universal Declaration, the offspring of a world desperately wanting to create a better world in the wake of the horrors of World War II stating in its first article: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’ – the economically oriented European Union has today offered its member states to ratify a Constitution which is nothing but the offspring of the evolution of the European Convention on Human Rights jurisprudence in the last three or four decades.

Many have doubts about whether the European Union Constitution will ever become a real legal tool as it must be ratified by every one of the 25 member state of the EU – the first two articles of that Constitution however seem like the final chapter of the well written chain novel, with drama, story line and a teleological outcome. All the same one may question whether all these words are more then empty rhetorical testimonials.

What do these concepts entail, to name for example the basic concept of human dignity which is protected in Article 1 of the German Constitution of 1949 but not mentioned in the Icelandic Constitution. Respect for human dignity is the very essence of the European Convention;1 hence the Court does not discard the context that the rights are exercised in. The individual dimension cannot be disengaged from the societal context. In its first freedom of expression case, the Court embraced the two strongest theoretical foundations for protecting freedom of expression as one of the ‘essential foundations of democratic society, one of the basic conditions for its progress and for the development of every man’.2

In the following years in – the cases that came before it – the Court gradually developed the context within which the press must operate in modern society. It emphasized the tolerance towards the dignity of others, the need for a pluralistic environment in the media landscape so that public discussion – the political duty of the press – would blossom – and eventually culminate in the broadminded society which was essential for the realization of human rights for all. The greatest menace to freedom is an inert people – said the famous American Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis in 1927. Inert people are politically passive – and it is the role of the press to stimulate these people, even to shock and offend them – since nothing corrodes the spirit of the politically active citizen more than the political indifference of those who only seek to cultivate their gardens’.

It is hard for the press to fulfil the expectations of the Court’s case law. When the press shocks and offends the public or parts of it – it may be hit back by the heavy hand of the law. A Danish journalist brought his case to Strasbourg when charged for dissemination of racist statements in a prime time television programme (interviewing young racist men who said niggers are not human beings, they are animals – referring to sections of immigrants living in Copenhagen). The Court in Strasbourg concluded that a law under which a journalist may be heavily penalized has a chilling effect on journalism

But the Court was divided: many of the judges were seriously offended by the decision accusing the majority of the Court for not taking into consideration the vulnerability of the targeted group – these judges reasoned that the protection of racial minorities could not have less weight than the right of journalists to impart information. This was the first time that the Court had to choose between the right of journalists to portray a picture of immigrants in Copenhagen – poorer people, less educated and so forth and safeguarding the valuable freedom of the press to speak its mind. The dissenting judges were harsh in their criticism of the majority’s decision. They said that a large group of persons had been denied the quality of human beings” In earlier decisions the Court has – in our view, rightly – underlined the great importance of the freedom of the press and the media in general for a democratic society, but it has never had to consider a situation in which ‘the reputation or rights of others’ (art. 10-2) were endangered to such an extent as here.

These judges reasoned that the protection of racial minorities could not have less weight than the right to impart information.4 The majority of the Court wanted on the other hand to shelter journalism from the pitfall of self-censorship in its coverage of controversial issues. It probably made the right decision in this case by distinguishing between a presentation, which is shocking and offensive– and the chilling effect of punishing journalists. Sometimes a provocative presentation of that kind is the only way to stir the public to do something about the problem and may in the end do more for the cause than a journalist hostage to censorship.

However, there is another side to this problem like always and that is the silencing effect that discriminating journalism may have on individuals, groups and even the whole of society – it is not only journalists who may be intimidated by sanctions but also the people who suffer because of the often brutal portrayal or picture that the media draws up of the minority that they belong to. In feminist legal theory the situation of minorities, black people, poor people – and women although they do not constitute a minority in the numerical sense is partly blamed on a gender biased media – a press which is in fact practicing inequality’.5 From this viewpoint pornography is not a question of freedom of expression but a question of equality – the right to equal treatment. Portraying women as sex objects or merely a stereo-type portrayal of women may have wide ranging effects for whole generations of young girls just like the portrayal of black men as lazy, laid-back and non-assertive may have wide ranging effects on whole generations of young black boys . The press becomes an oppressive tool if it does not take these things into consideration.

I will end this brief talk which is really about the dialogue between the press and society with a question – like the several questions posed under the heading of this workshop. The feminist law professor Catherine Mckinnon asks whether is it a

4 In the view of the majority the essence of the decision was to prevent a chilling effect on journalism. It is hence doubtful to infer from this decision that the Court is in favour of complete press autonomy, although it eludes the impact of derogatory comments on the dignity of the minorities attacked. The Court was not emphasizing the principle of freedom of expression as a constitutive end but rather as an instrumental interpretation of Article 10.

I will end this brief talk which is really about the dialogue between the press and society with a question – like the several questions posed under the heading of this workshop. The feminist law professor Catherine Mckinnon asks whether is it a coincidence that so many black children go hungry to bed every night – and for the same reason it may be questioned why on earth in one of the richest societies namely Iceland – the children of 31 per cent of single mothers, according to official statistics, are living below the poverty line according to official statistics.6 Half the worlds’ children go to bed hungry. According to a news story on the BBC a few days ago quoting a UN report 17 000 children die every day from hunger-related diseases. A UN specialist on world hunger called the situation a scandal in a world that is richer than ever before. Calling attention to such scandals – is one of the tasks of the press. The BBC quoted the UN specialist saying that: “The silent daily massacre by hunger is a form of murder. It must be battled and eliminated.” This is why the press may not remain silent – independent of the political and business interests at stake – and there is no media company of relevance that does not have to take such interests into consideration.

Freedom of the press is the touchstone freedom of all other freedoms, including the right to life – ‘on close inspection it turns out that only in a society where there is critical media reflecting the whole spectrum of political opinions and ideologies – where there is constant vigilance and questioning of prevailing views, where the voice in the desert is heard – is dissent possible: not just possible but vital’.7 We are what we are through our relationship to others, said George Herbert Mead. Today that relationship takes place through the worlds’ media. And that is a deep cause for concern – and of course a challenge for those who have what US Supreme Court Justice Brandeis called the essence of liberty, that is courage! One of the men who wrote the European Convention on Human Rights, famous French legal scholar Pierre Henry Teitgen said back in 1949:

We must have the courage to recognize that freedom of money, of competition and of profit has sometimes threatened to destroy the freedom of men. In such a case I may recall the saying of Larcordaire, that it is freedom, which enslaves and law that liberates.8

2 Handyside v. the United Kingdom, supra note 91, § 49.

3 In earlier decisions the Court has – in our view, rightly – underlined the great importance of the freedom of the press and the media in general for a democratic society, but it has never had to consider a situation in which ‘the reputation or rights of others’ (art. 10-2) were endangered to such an extent as here.

4 In the view of the majority the essence of the decision was to prevent a chilling effect on journalism. It is hence doubtful to infer from this decision that the Court is in favour of complete press autonomy, although it eludes the impact of derogatory comments on the dignity of the minorities attacked. The Court was not emphasizing the principle of freedom of expression as a constitutive end but rather as an instrumental interpretation of Article 10.

5 MacKinnon, supra note, p. 107.

6 Single mothers in Iceland are around 12 thousand – single fathers a little under 900.

7 Bobbio, p. 60.

8 In August 1949 in a Motion to recommend to the Committee of Ministers, an organization within the Council of Europe to ensure the collective guarantee of human rights proposed by Mr. Teitgen, Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe and other representatives. The birth pains of the Convention were not easy. The first initiative had been taken by the unofficial European Movement. The International Juridical Section of the European Movement was set up under the chairmanship of M. Pierre-Henri Teitgen, with Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe and Professor Fernand Dehousse as joint rapporteurs. This body produced a draft European Convention on Human Rights and a draft Statute of the European