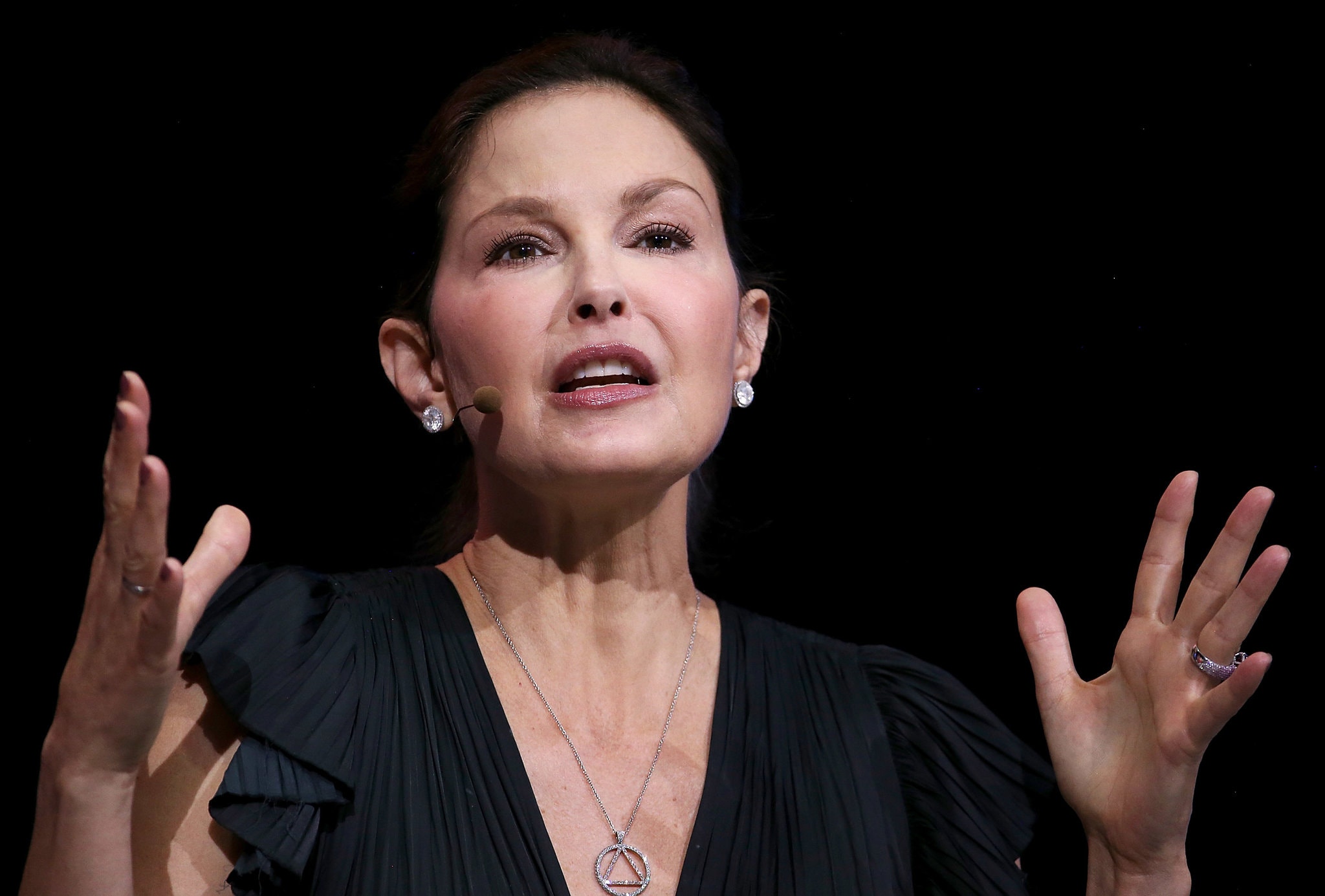

Ashley Judd was one of the first women to attach her name to accusations of sexual misconduct against Harvey Weinstein, but like many of the claims that followed, her account of intimidating sexual advances was too old to bring Mr. Weinstein to court over.

Then a legal window opened to her. After reading about a director’s claim that Mr. Weinstein’s studio, Miramax, had described Ms. Judd as a “nightmare to work with,” she sued the producer for defamation in 2018.

Ashley Judd could not successfully sue Harvey Weinstein for sexual harassment, but like other women with claims against powerful men, she turned to a defamation lawsuit

Mr. Weinstein’s rape trial in Manhattan, which began with jury selection last week, is a spectacle not only because he is the avatar of the #MeToo era, but also because it is one of the few sexual assault cases to surface with allegations recent enough to result in criminal charges.

So, unable to pursue justice directly, women and men on both sides of #MeToo are embracing the centuries-old tool of defamation lawsuits, opening an alternative legal battleground for accusations of sexual misconduct.

While the facts of the cases vary, the plaintiffs are generally using defamation law not just for its usual purpose — to dissuade damaging speech about them — but also as a tool to enlist the courts to endorse their version of disputed events.

This year, key verdicts are expected in defamation cases involving President Trump, the Senate candidate Roy Moore and the actor Johnny Depp, and lawyers are watching the proceedings closely.

In some cases, women are basing their suits on recent statements in which the men they accused called them liars; or in Ms. Judd’s case, on a disparaging statement she said she was not aware of until the director, Peter Jackson, revealed it in a 2017 interview. Men like Mr. Depp are using defamation suits to fend off allegations from women, in his case, his ex-wife Amber Heard, who accused him of domestic abuse.

Courts have only begun to grapple with this #MeToo-inspired wave of defamation lawsuits, which are, in some cases, being brought because the statutes of limitations on sexual misconduct can be as short as one year, depending on the state and severity of the accusation. Those statutes are a bedrock legal concept designed to discourage people from being sued or imprisoned based on witness memories that may have eroded over the years.

The cases raise a swirl of issues, including the appropriate limits on freedom of speech; the power of social media, where an accusation can spread on platforms that vary in reliability and authority; and whether the statutes of limitations should be extended, as some states have already done.

Advocates on both sides are anxious. Lawyers for people accused of misconduct fear that a string of defamation victories for women will prevent men who believe they have been wrongly accused from freely defending themselves. At the same time, backers of the #MeToo movement fear that a spate of defamation cases against women will push victims back into the shadows.

“The next year is going to be very interesting when it comes to the law of defamation,” said Sigrid McCawley, a lawyer representing Virginia Giuffre, who said she was a victim of Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking operation and accused Mr. Epstein’s ex-girlfriend Ghislaine Maxwell and the lawyer Alan Dershowitz of being part of it. After they issued statements saying she was lying, she sued them for defamation. Mr. Dershowitz has countersued Ms. Giuffre for defamation; Ms. Maxwell settled in 2017.

“We’re going to see a wave of opinions that will shape that landscape quite a bit,” Ms. McCawley said.

Several cases involve big names in politics and entertainment. Summer Zervos, a former “Apprentice” contestant, filed a defamation lawsuit against Mr. Trump for his comments during his presidential campaign that her accusations of unwanted kissing and groping were fabricated. The president has argued that he cannot be sued in state court while in office, an issue that is likely headed for New York’s highest court. Its decision will be closely watched by E. Jean Carroll, who filed a similar claim against Mr. Trump after he said that she had lied about his raping her to increase sales of her new book.

Leigh Corfman, who accused Mr. Moore of touching her sexuallywhen she was 14, sued him for defamation after he called her story false, malicious and “politically motivated.” That trial is expected to start this year in Alabama. Mr. Moore lost his Senate race in 2017 after accusations surfaced from Ms. Corfman and other women.

And last year, at least eight women reached settlements with Bill Cosby’s insurance company to end their defamation lawsuits. They filed them after his representatives accused them of lying when they said Mr. Cosby had sexually assaulted them decades ago.

At the same time, defamation suits are a go-to strategy for accused men trying to preserve their reputations. Mr. Depp’s lawsuit is expected to go to trial this summer in Virginia unless the judge dismisses it. And a judge in Brooklyn is considering whether to allow or throw out a lawsuit filed by the writer Stephen Elliott against Moira Donegan, the creator of a widely circulated list of men accused of sexual misconduct that included him.

The author Stephen Elliott in 2012. After his name appeared on a crowdsourced list of men accused of sexual misconduct, he sued the creator of the list.Credit…

Mr. Elliott, 48, who denied having assaulted anyone, said in an interview that after his essay about the accusation was rebuffed by mainstream news outlets and with his career in shambles, he saw a defamation lawsuit as his only option.

“What would you do if you had been falsely accused of rape?” he said.

There are lower-profile cases moving through the courts, too. Thirty-three out of 193 cases that the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund supports involve defending workers who came forward about sexual harassment and were then sued for defamation, said Sharyn Tejani, the fund’s director.

For many plaintiffs, a benefit of suing for defamation is the opportunity to air the facts of what happened years ago, even if they are unable to sue for harassment or assault.

“In order to prove you’re a truth teller, you have to prove it happened,” said Joseph Cammarata, who represented seven Cosby accusers. “This is a direct way to get at the person who assaulted you.”

In Ms. Judd’s case, it could lead to a hearing over her account of visiting Mr. Weinstein’s room at the Peninsula Beverly Hills hotel one morning in late 1996 or early 1997, expecting a professional breakfast. She said that Mr. Weinstein, wearing a bathrobe, had requested to massage her or for her to watch him shower, and that she had refused.

Ms. Judd has argued that Miramax called her a “nightmare to work with” in retaliation for the hotel encounter. Miramax’s alleged conversation with Mr. Jackson occurred more than 20 years ago. The statute of limitations for a defamation claim in California is just one year, but the judge let the case go forward, saying that it was plausible that Ms. Judd would only learn about the conversation through Mr. Jackson’s 2017 interview. (The judge threw out Ms. Judd’s sexual harassment claim, saying it did not fall within the scope of California law.)

Mr. Weinstein has not directly disputed the allegation that Miramax said Ms. Judd was a “nightmare to work with” but has argued that his attempts to land her major acting roles later on showed that he was not trying to hinder her career. He has denied having any nonconsensual sexual encounters, including with the two women at the center of his rape trial in Manhattan. On Monday, prosecutors in Los Angeles announced that he had been charged with rape and sexual battery in connection with encounters with two women there.

Compared with some other countries, in the United States a defamation case is relatively difficult to win, because of a standard set by the Supreme Court to protect freedom of the press. If the plaintiff is a public figure, as many are, he or she must prove the statement was both false and made with “reckless disregard” for whether it was true.

In countries without the same high bar, including China, Australiaand France, men have won high-profile defamation cases against women or news outlets that published their stories.

In the United States, a court must also find that the speech in question is based in fact and not purely opinion. Part of Mr. Trump’s argument against Ms. Zervos is that his statements were “fiery rhetoric, hyperbole and opinion” that are protected by the Constitution. Mr. Moore has made a similar argument. In denying Mr. Trump’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, a judge wrote that he knew exactly what transpired between him and Ms. Zervos, so his calling her a liar was akin to an assertion of fact.

The public airing of #MeToo stories over the past two years has made these suits noticeable, but the strategy is not entirely new. In 1994, Paula Jones sued President Bill Clinton alleging that he had exposed himself to her when he was governor of Arkansas. One portion of the lawsuit accused him and his associates of defaming Ms. Jones by characterizing her as a liar.

A judge dismissed the claim, writing that the comments were “mere denials of the allegations and the questioning of plaintiff’s motives.” Mr. Clinton settled the rest of the suit for $850,000, without admitting wrongdoing; his lying about his affair with Monica Lewinsky during the Jones lawsuit led to his impeachment.

But a more recent ruling, by New York’s highest court, has given hope to lawyers representing women. The court in 2014 revived a lawsuit filed by two men against Jim Boeheim, the Syracuse University basketball coach, who had accused the two men of lying when they said one of Mr. Boeheim’s assistants, Bernie Fine, had abused them as children. The defamation lawsuit was settled in 2015. (Mr. Fine lost his job, but after an investigation, he was not charged with a crime.)

The decision made the New York court system an attractive place to file this kind of lawsuit, said Mariann Wang, who represented the plaintiffs in that case, and Ms. Zervos until recently.

Since the #MeToo movement took off, a number of states have lengthened the statutes of limitations for sexual assault claims, meaning future victims may have less need to rely on defamation lawsuits.

But those suits remain the only legal option for people like Therese Serignese, who said Mr. Cosby gave her pills backstage at a show in Las Vegas in 1976, when she was 19. The next memory she had was waking up to realize that she was being sexually violated.

She joined a lawsuit in 2015 asserting that representatives for Mr. Cosby had defamed her and other women by calling stories like theirs “fantastical” and “past the point of absurdity.” Mr. Cosby’s insurance company settled the lawsuit in April, about a year after he was convicted of sexual assault.

“My point was to make him accountable,” Ms. Serignese, 62, said. “Put him out there and make him work to prove that I’m not telling the truth. Because I knew I was telling the truth.”